North Korea dismayed observers (or simply fulfilled the observers’ basic assumption of North Korean trustworthiness) Sept. 20 with a statement from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs seeming to renege on the six-party joint statement signed only a day earlier. In the Ministry statement, the unidentified spokesman said

“We made it clear that the basis of finding a solution to the nuclear issue between the DPRK and the U.S. is to wipe out the distrust historically created between the two countries and a physical groundwork for building bilateral confidence is none other than the U.S. provision of LWRs to the DPRK.”The translation is that North Korea won’t believe Washington recognizes Pyongyang’s right to a civilian nuclear program until Washington provides such a program. This, I guess, would be a case of “action for commitment,” as opposed to the “commitment for commitment, action for action” as written in the six-party agreement.

The spokesman further expounds upon this line by adding

“As clarified in the joint statement, we will return to the NPT and sign the Safeguards Agreement with the IAEA and comply with it immediately upon the U.S. provision of LWRs, a basis of confidence-building, to us.”Now, given that the next round of talks isn’t slated until November, Pyongyang may simply be trying to take any wind out of the U.S. administration sails should Washington try to tout a victory over North Korea’s nuclear ambitions. Given troubles at home for Bush, even a tiny foreign policy victory would be welcome, but with Hurricane Rita filling the airwaves, the resolution (sort of) of nearly three years of nuclear negotiations gets short shrift on the cable networks.

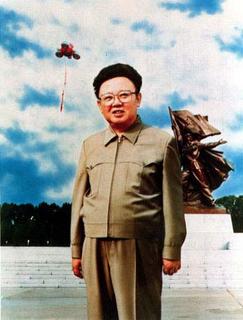

Another alternative is that Pyongyang is truly trying to tank the deal. Yonhap is reporting an unnamed South Korean official as saying that Kim Jong Il told Unification Minister Chung Dong Young that North Korea would draw out the nuclear uncertainties until the end of the Bush term – three years from now. Of course, the unnamed official may simply be perturbed at the attention North Korea is getting from President Roh, and concerned about the massive economic push Roh is seeking to build up the North.

And this brings to another possibility. Pyongyang feels pretty confident right now. It managed to get a deal that largely ensures its interests without trading much in return. The structure of the six-party agreement leaves economic and energy issues in the hands of individual states rather than in a multi-party format. (See point 3: The six parties undertook to promote economic cooperation in the fields of energy, trade and investment, bilaterally and/or multilaterally.)

This means that, unlike the 1994 Agreed Framework, which put the KEDO reactors in the hands of a multinational consortium, where one nation’s non-participation would negate the involvement of the others, the new agreement doesn’t so much trade the denuclearization of North Korea for a specific raft of multi-national projects as much as it creates a process where both occur – not necessarily contingent upon one-another’s timing.

Thus South Korea can accelerate its bilateral cooperation with the North as part of its own aim to strengthen the North Korean economic and social system in preparation for eventual unification even as Washington and Pyongyang bicker over the timing or existence of light water reactors. Pyongyang has removed Washington as the key to all future economic, political and security dialogue. And Seoul is seeking to exploit this to enhance its own role as the mediator between Pyongyang and Washington, rather than sit on the sidelines and follow the U.S. lead (or be overtaken by the U.S. initiatives).

This creates an interesting dynamic on the Korean Peninsula, one in which North Korea’s security is, to a large degree, ensured by South Korea, whose cooperation would be necessary for any U.S. military action against North Korea. China and Russia are less important players to Pyongyang, though the North will continue to seek to exploit those relationships, but with Beijing, for example, trying to use North Korea as a lever with Washington, Pyongyang has to some extent extricated itself from the additional Chinese coercion.

Ultimately, this may set up South Korea and Washington for a deeper confrontation, or simply convince Washington to walk away again for a while and leave Seoul to manage Pyongyang. And this would leave president Roh, who is weak at home, as the pivot of Northeast Asian security for his remaining years in office.

No comments:

Post a Comment